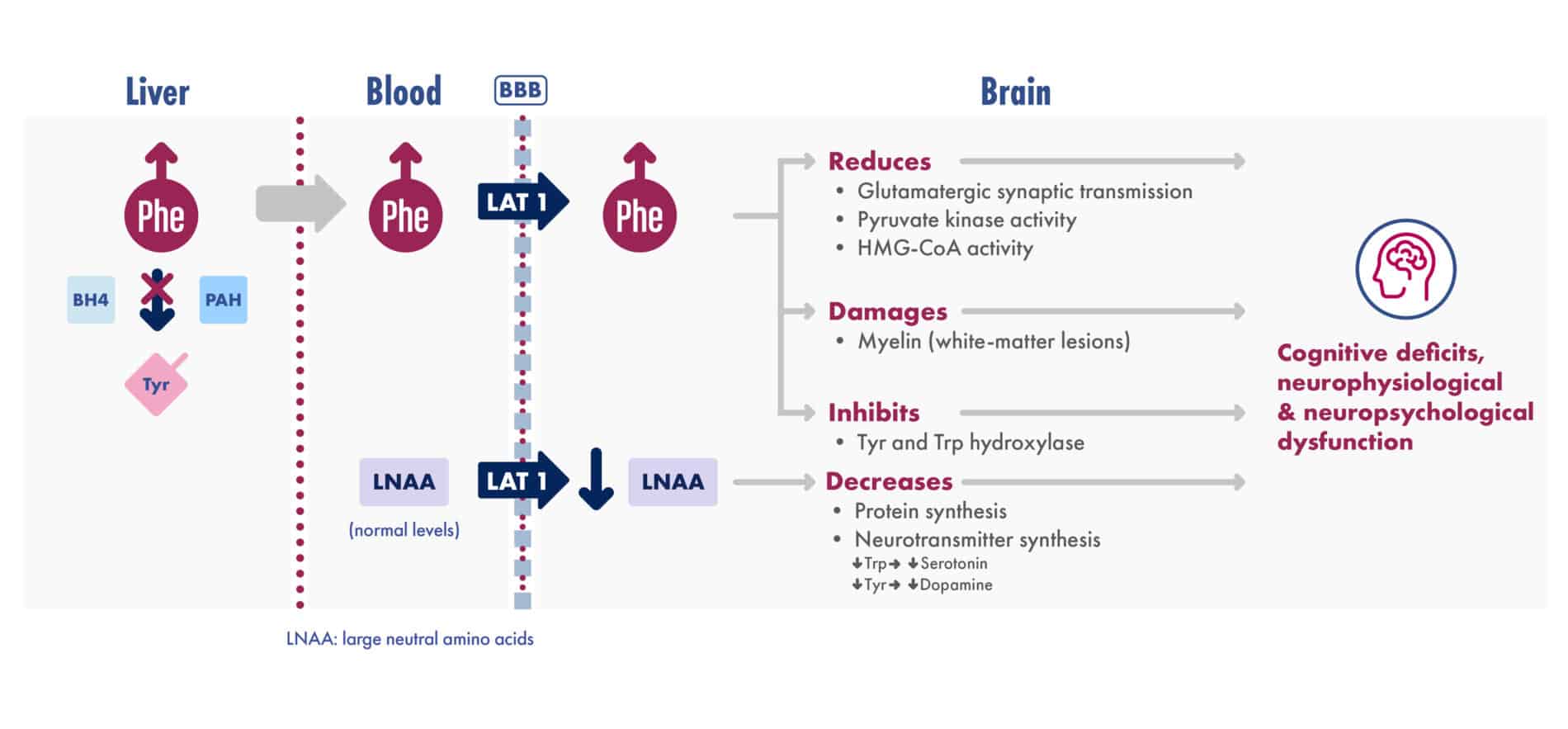

Adapted from van Spronsen et al. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021

References: 1. Ashe K, Kelso W, Farrand S, et al. Psychiatric and cognitive aspects of phenylketonuria: the limitations of diet and promise of new treatments. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:561. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00561. 2. Vockley J, Andersson HC, Antshel KM, et al. American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics Therapeutic Committee. Phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency: diagnosis and management guidelines. Genet Med. 2014;16(2):188-200. 3. Blau N, van Spronsen FJ, Levy HL. Phenylketonuria. Lancet. 2010;376(9750):1417-1427. 4. Rocha JC, MacDonald A. Treatment options and dietary supplements for patients with phenylketonuria. Expert Opin Orphan Drugs. 2018;6(11):667-681. 5. van Wegberg AMJ, MacDonald A, Ahring K, et al. The complete European guidelines of phenylketonuria: diagnosis and treatment. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12(1):162. doi:10.1186/s13023-017-0685-2. 6. van Spronsen FJ, Blau N, Harding C, et al. Phenylketonuria. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):36. doi:10.1038/s41572-021-00267-0. 7. Anderson PJ, Leuzzi V. White matter pathology in phenylketonuria. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;99(suppl 1):S3-S9. 8. Christ SE, Price MH, Bodner KE, Saville C, Moffitt AJ, Peck D. Morphometric analysis of gray matter integrity in individuals with early-treated phenylketonuria. Mol Genet Metab. 2016;118(1):3-8. 9. White DA, Antenor-Dorsey JV, Grange DK, et al. White matter integrity and executive abilities following treatment with tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) in individuals with phenylketonuria. Mol Genet Metab. 2013;110(3):213–217. 10. Schuck PF, Malgarin F, Cararo JH, Cardoso F, Streck EL, Ferreira GC. Phenylketonuria pathophysiology: on the role of metabolic alterations. Aging Dis. 2016;6(5):390-399. 11. Adler-Abramovich L, Vaks L, Carny O, et al. Phenylalanine assembly into toxic fibrils suggest amyloid etiology in phenylketonuria. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8(8):701-706.